To spark or not to spark

- Analog

- 2023-09-23 21:19:11

Anybody who has ever watched a thunderstorm knows what sparks can do under the right circumstances, the same goes for anyone who has ever watched the Boris Karloff movie, “Frankenstein”. However, improperly extrapolating those observations to the lab bench is not a good idea.

I’m going to vent a little bit here so get ready.

There was this microwave power meter which was having operational failures that had been wrongly blamed on damages to its power sensing thermistors. That was not actually the case. The thermistors themselves were not being harmed by anything.

Eventually I made circuit design revisions which solved the operating problem at hand. But until that was done, fictitious suppositions were being improperly bandied about the company and, to use a common vernacular, “They had legs.”

A falsehood can go around the globe ten times while the truth is still trying to leave the parking lot.

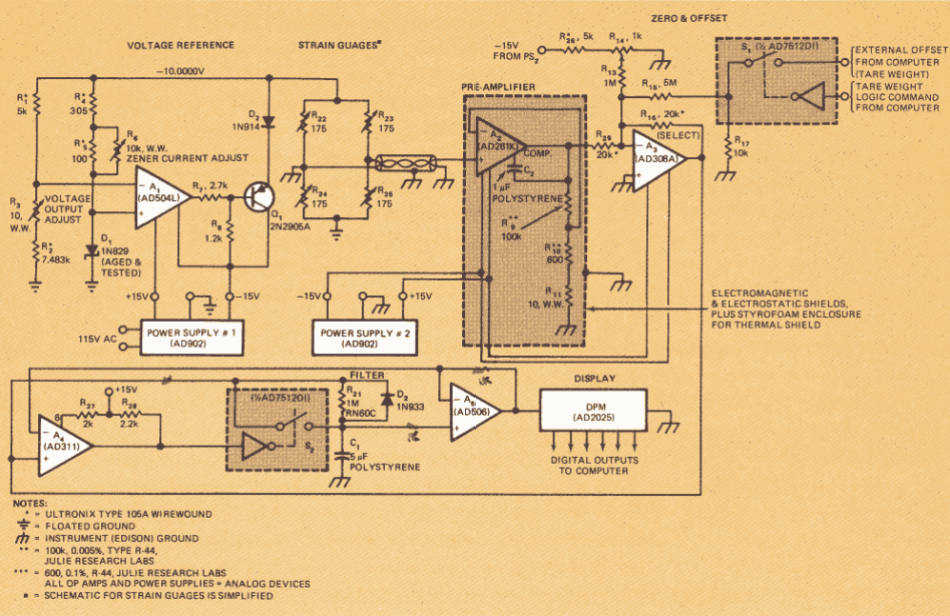

Thermistor power was actually quite low with DC bias currents down in the milliamp range. Unfortunately, an ill-informed colleague spread a story to inept company management saying that when energized, the thermistor assemblies were being disconnected by unplugging them from their cable connectors, sparks were occurring at the parting connector pins and that those sparks were delivering damaging energy to the thermistors (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The incorrect thesis on why the microwave power meter was having operational failures. Source: John Dunn

If there had been any sparking going on as in Figure 1, the impedance(s) of those sparks would have arisen in series with the impedances of the thermistor, the resistances of the wires, the source impedance of the driving amplifier and the input impedance of the monitoring circuitry.

Such hypothetical sparks would not suddenly be dumping some stored reserve of energy. Whatever current might have been flowing just before connector pin separation could only go downward, not upward. Thus, the thermistors were quite safe from that alleged source of harm.

Even so, the company’s technologically inept management (I could have used more accurately descriptive though less polite terminology) was led to believe that there must somehow have been some kind of destructive energy discharge events going on like the ½LI² of an automobile ignition coil getting suddenly open circuited or the ½CV² of a charged capacitor getting suddenly short circuited. Management became utterly and wrongly convinced that I just wasn’t looking at the issue properly.

Actually, the thermistor monitoring circuits were themselves at fault which was the problem I fixed while ignoring my colleague and while ignoring management. I made several design revisions which corrected several operational problems.

The outcome was a success! Everything worked okay from then on.

“Truth always prevails in the end.” -Lord Acton, English Thinker, Editor and Professor of Modern History at Cambridge University, 1834-1902.

Of course, when the truth does not prevail…

John Dunn is an electronics consultant, and a graduate of The Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn (BSEE) and of New York University (MSEE).

Related Content

Meditations on photomultipliersDon’t send a man to do a meter’s jobUsing a power accumulator for real-time power measurementsGood codeTo spark or not to spark由Voice of the EngineerAnalogColumn releasethank you for your recognition of Voice of the Engineer and for our original works As well as the favor of the article, you are very welcome to share it on your personal website or circle of friends, but please indicate the source of the article when reprinting it.“To spark or not to spark”